Downtown

Edmonton’s downtown has always been the heart of the city, and yet has struggled through more than one attempt to reinvent itself.

Edmonton’s downtown has always been the heart of the city, and yet has struggled through more than one attempt to reinvent itself.

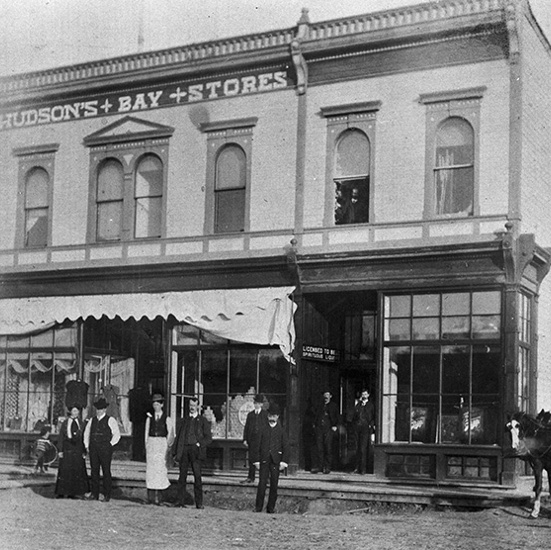

Before Dominion Land Surveyors arrived in 1882, about 200 people lived and worked in Fort Edmonton. A few made their homes on land around the fort, like Kenneth McDonald and his brother-in-law William Rowland who claimed land in what is now Riverdale. Government surveyors formalized many of these pre-existing homesteads and defined new ones, but one of their primary tasks was to circumscribe the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) reserve. When the HBC handed over their possession of Rupert’s Land to the Dominion of Canada in 1870 they were able to retain 3,000 acres of land around each of their forts. The HBC reserve around Fort Edmonton spanned from what is now 101 Street to 121 Street, and from the North Saskatchewan River to 118 Avenue.

Within a few years the town of Edmonton grew up east of the reserve along Jasper Avenue - the 100-foot main street surveyed to run as near as possible between the Methodist mission on the east and the Anglican mission on the west. Because the street headed straight for the old fur trading post in the mountains they called it Jasper Avenue. Originally the town centred along Jasper and Namayo Avenue (97 Street). However, with the 1882 survey, the HBC began to subdivide its reserve and private development pushed further south and west.

The arrival of the Calgary and Edmonton (C&E) Railway on the south banks of the river in 1891 triggered the formation of South Edmonton (later named Strathcona) and disconcerted Edmontonians quickly incorporated as a town in 1892. Rivalry between the two communities continued as both grew rapidly with the influx of settlers brought in by rail, but in 1912 the two cities amalgamated on more or less good terms.

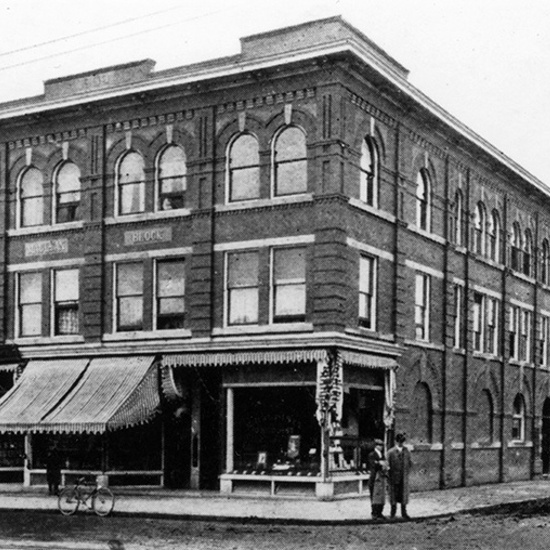

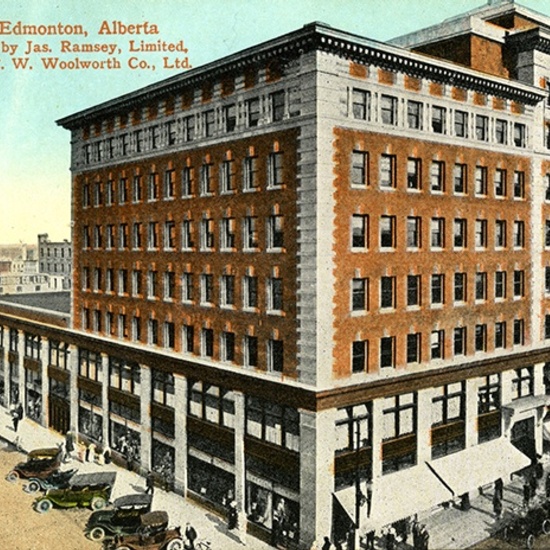

Early construction along Jasper Avenue consisted of mainly false-fronted wooden buildings. Edmonton’s population was just over 2,000 people in 1899. Within ten years the population was over ten times that and sturdy brick, concrete, and steel buildings became the norm. Built in 1909, the three-storey brick Jasper Block on 105 Street is a good early example of local architecture and one of the oldest buildings downtown.

Local railways significantly shaped the core of Edmonton. The Canadian Northern Railway (CNoR) connected to the C&E in Strathcona and crossed the Low Level Bridge for the first time in 1902. The warehouse district on the historic western edge of downtown grew up along the CNoR and later Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) spur lines that delivered to the storage facilities for the businesses along Jasper Avenue. Remnants of this district are seen in the uncomplicated brick buildings still standing along 104 Street. The commercial style Phillips Building on 104 Street and 101 Avenue was first used by the Western and Cartage Company in 1912 as storage and exemplifies Edmonton’s early warehouses.

Edmonton’s downtown is bounded by Oliver to the west along the CPR land corridor just west of 109 Street; Queen Mary Park and Central McDougall to the north along 105 Avenue; McCauley, Boyle Street-The Quarters to the east along 97 Street; and Rossdale and the banks of the North Saskatchewan River valley to the south. This area was relatively developed by 1912 when the HBC sold off the rest of its reserve at the height of the local economic boom. Further development progressed slowly for the next three decades however, as the city endured a recession, two wars, and the depression of the 1930s.

When the Second World War ended and with the discovery of oil in Alberta in 1947, boom times returned and the city began to reinvent itself. Car ownership exploded with cheap gas and plenty of jobs. Edmonton was faced with crowded downtown streets and pressure on the road and transportation system. The city responded with new roads and new suburbs drawing residents out of the now more expensive downtown. Suburban shopping malls, starting with Westmount Mall in 1955, encouraged major retailers out of the core, and downtown shops with easy-access street entrances gave way to high-rises connected with pedways and retail areas hidden behind the tower doors. Many heritage buildings were destroyed in the name of cost saving measures and progress.

The St. John’s Edmonton Report of 1974 touted that development was coming in the shape of high-rises with a “rebirth of new construction in what is described as the most fantastic economy in North America”. Dozens of new buildings reframed Edmonton’s skyline by 1970 including the Chateau Lacombe, Centennial Building, CN Tower, City Hall, Chancery Hall, and the Centennial Library. And a downtown mall was in the works. The cost of this redevelopment however was foreseen in 1979 by a downtown housing study: “the residential potential of large areas of downtown is being eroded by recent rapid escalation of land prices… with inadequate attention to street, building, and precinct quality also acting to dissuade housing. If no actions are taken… it is likely that Edmonton will quickly develop a centre that is almost solely devoted to office and institutional function, with the problems that such centres have been shown to bring… In general, downtown is becoming increasingly uni-functional as an area that is devoted to financial and other office functions.”

With no previous over-riding principals to govern downtown development the city began of series of plans to revitalize the area starting in the early 1980s. However, even as hopes were inspired by the architectural achievements of new facilities like Grant MacEwan Community College, the Convention Centre, and the Winspear Centre, the core’s population fell from 8,100 to 6,200 between the 1970s to the 1990s, and vacancy rates skyrocketed. Edmonton’s downtown also took a major blow in the early 1990s when the city lost up to 10,000 provincial government jobs some buildings were left virtually empty.

Rejuvenation began, albeit slowly, with the 1997 Downtown Redevelopment Plan (DRP), since revised in 2010. The downtown population grew beyond 13,000 by 2015 and people seemed to be responding accordingly. The DRP created incentives designed to get people living, shopping, and working downtown again. One-way corridors once created to ease traffic congestion downtown returned to the more pedestrian-friendly two-way streets. With their hopes pinned on dozens of major new developments, the city’s vision included greater environmental sustainability, increasing public transit use, improving storefronts and street friendliness, and the retention and retrofitting of heritage buildings. The reinvigorated Mercer Warehouse on the now vibrant 104 Street is a success story many hope will inspire others.

Details

Sub Division Date

TBA

Structures

Agency Building

Alberta Hotel

Alberta Legislature Building

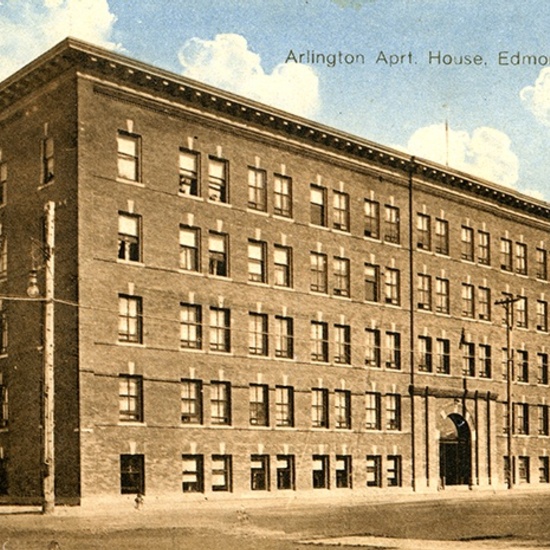

Arlington Apartments

Armstrong Block

Birks Building

Bowker Building

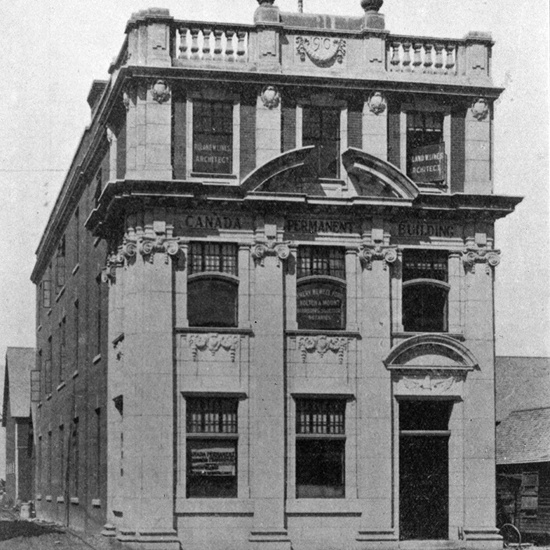

Canada Permanent Building

Canadian National Railway Station-1928

Canadian Northern Railway Station-1905

Capitol Theatre

Churchill Wire Centre

Civic Block

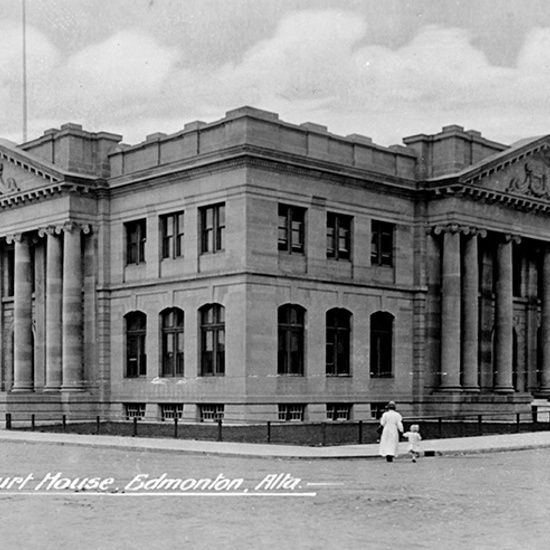

Court House

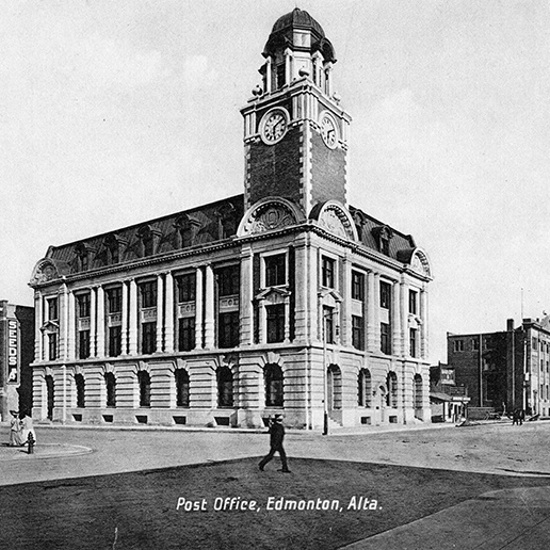

Downtown Post Office

Edmonton Art Gallery

Edmonton Club

Edmonton Cold Storage Company, Ltd.

Edmonton Public Library

El Mirador Apartments

Empire Block

Federal Building

First Presbyterian Church

Gariepy Block

Gariepy Mansion/Rosary Hall

H.V. Shaw Building

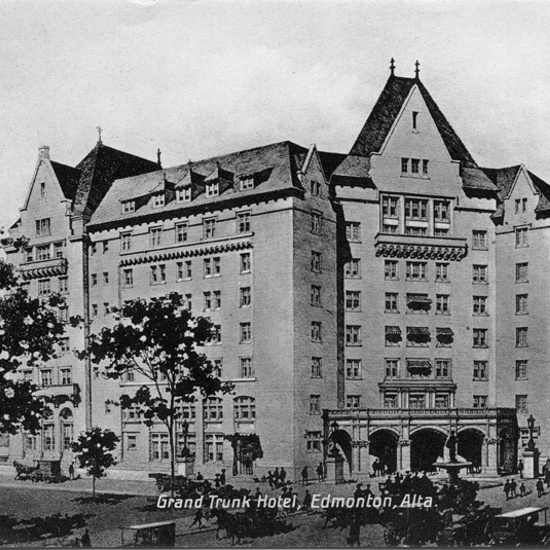

Hotel Macdonald

Hudson's Bay Company Building

Imperial Bank

Imperial Bank of Canada Building

Law Courts

MacLean Block

Masonic Temple- Saskatchewan Lodge #92

McDougall Mansion

McLeod Building

Mercer Warehouse

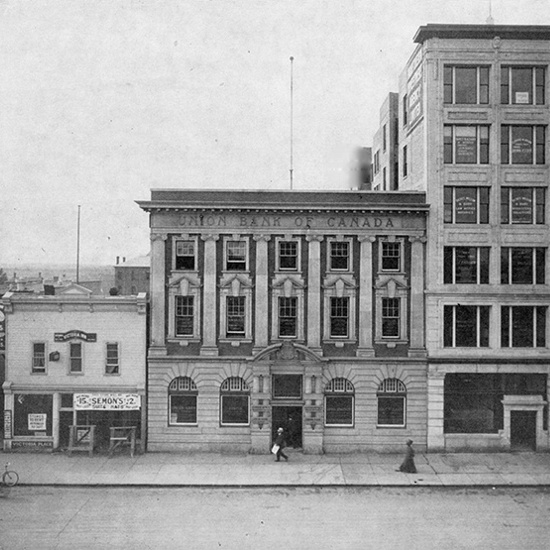

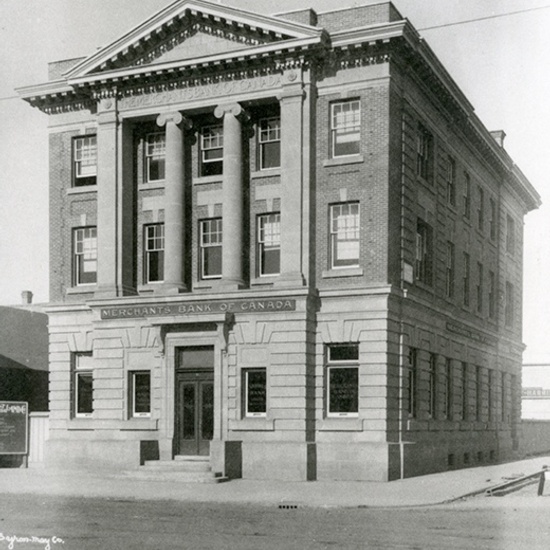

Merchants Bank of Canada

Moser and Ryder Block

Pantages Theatre

Salvation Army Citadel

Secord House

Stocks Residence

Tegler Building

Architects

Robert Percy Barnes

Richard Palin Blakey

William G. Blakey

Cecil Burgess

Alfred Marigon Calderon

Taylor, Hogle and Davis

Franz Xavier Deggendorfer

Maxwell Dewar

John Dow

William Somerville Edmiston

H.L. Gage

David Hardie

Henry Denny Johnson

Percy Nobbs

George Hyde

Don Bittorf

Gordon Wynn

Peter Rule

John Rule

Arthur Everett

Jock Bell

Roland Lines

Fred H. MacDonald

George Heath Macdonald

Ross MacFarlane

Herbert Alton Magoon

Allan Merrick Jeffers

H. J. Moore

Ralph Benjamin Pratt

John Schofield

Dewar, Stevenson, and Stanley

Ralph Henry Trouth

Unknown

Rick Wilkin

James Edward Wize

Bittorf and Wensley Architects

MacDonald & Magoon Architects

Nobbs & Hyde

Ross & Macdonald Architects

Rule Wynn Rule

Wilson and Herrald Architects