Oliver

Edmonton's original 'West End" is one of the city's oldest, and is one of the most densely populated communities.

Edmonton's original 'West End" is one of the city's oldest, and is one of the most densely populated communities.

In 1870 the Dominion of Canada purchased most of the land claimed by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). The agreement allowed the HBC to retain land reserves around each of its forts. The HBC selected all 3,000 acres of its reserve land at Fort Edmonton north of the North Saskatchewan River from what is now 101 Street to 121 Street, and from the river to 118 Avenue. As settlement arose, the HBC reserve and the land the company subsequently subdivided and sold greatly dictated the physical confines of the growing town of Edmonton.

In 1882, Malcolm Groat claimed 900 acres of land - River Lot 2 - bordering the western edge of the HBC reserve from what is now 121 Street to 149 Street, and from the river valley to 111 Avenue. An HBC employee since 1861, Groat retired from life in the fort in 1878 to homestead his claim. His river lot was the inception of what is now the Oliver district bounded by 109 Street, 124 Street, the North Saskatchewan River, and 104 Avenue.

Development of the district began when Groat donated land for both the newly arrived Anglican priest and the established Oblate mission. By the early 1900s, the area supported the Misericordia Hospital, the General Hospital, eight churches, and five schools. The Oblate missionaries became the first residents of the district in 1898.

Speculating on a population boom, Ontario lawyer William G. Tretheway purchased most of Groat’s farm for $100 per acre in 1903 and subdivided lots into a grid pattern. However, because of the remaining HBC reserve, these lots were separated from downtown Edmonton by an undeveloped expanse, especially to those travelling on foot. Tretheway and his partner R.P. Inglis convinced city council - in part with a $10,000 deposit - to grant them the charter to construct a streetcar system to the city’s western edge. Their plan never got off the ground. The dream, however, was taken up by James Carruthers and Henry Round who purchased the entire subdivision and replaced the deteriorating bridges over Groat Ravine, the 139th street ravine, and Stony Plain Road. In exchange, the city brought the streetcar line all the way to 21st Street (121 Street) and ensured the success of the district’s development.

In 1937 the area was officially named for Oliver School, built in 1911. The school was named after prominent Edmontonian Frank Oliver, founder of the first local newspaper, the Edmonton Bulletin. Oliver became the first local territorial and federal representative, and a national railway commissioner.

Wealthier individuals like Dame Eliza Chenier at 9926-112 Street built large fashionable four-square and Queen Anne style homes on the tree-lined boulevards framing the southern and western limits of Oliver. Less ornate bungalows housing middle and working class families filled in the blocks to the north. All were attracted to the close proximity to downtown, the stunning beauty of the river valley, and the extensive local educational, religious, and recreational opportunities. The Oliver district is shared by major Catholic, protestant, and Jewish communities; a prominent French quarter; and extensive commercial space.

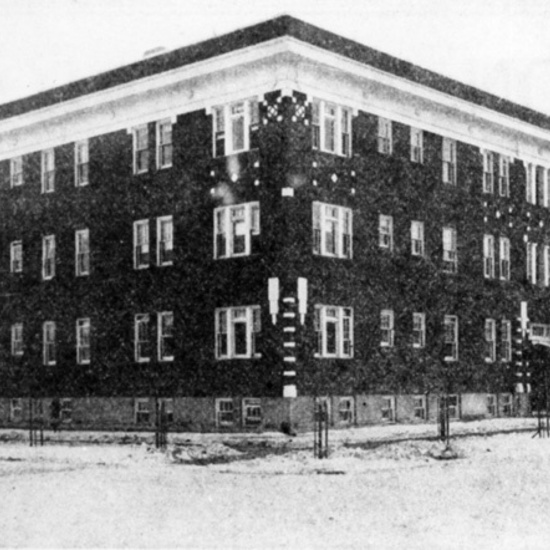

Sustained city growth has presented considerable challenges to the area. Oliver is Edmonton’s most populous neighbourhood housing more than 15,000 residents, and one of the neighbourhoods with the highest density. Most dwellings in Oliver were built after 1960 and many single family homes in Oliver have since been converted to low-rise apartments. The Valleyview Manor at 122 Street and Jasper Avenue is an early example of this densification. A high-rise boom in the 1980s brought on frequent and well-publicized fights between residents and developers. As well, through traffic to downtown cuts through prime residential areas and the city has implemented traffic control measures in the district. Some argue that these issues have led to an extensive loss of a sense of community in the district.

Oliver is the city’s most diverse neighbourhood in terms of development. Residents live in everything from single detached homes to high-rise apartments. They work in neighbourhood commercial shops or local high-rise office towers. And yet the city’s original ‘West End’ has managed to retain a great deal of character. Some of Edmonton’s most interesting Edwardian and classically inspired architecture can be seen in the luxury and working class apartments that remain from the early twentieth century; Oliver’s first fire hall is now an apartment building; and beautiful streetscapes of period housing have become local landmarks.

Details

Sub Division Date

TBA

Structures

Balfour Manor

Beth Shalom Synagogue

Christ Church

Cristall House

Dame Eliza Chenier Residence

Le Marchand Mansion

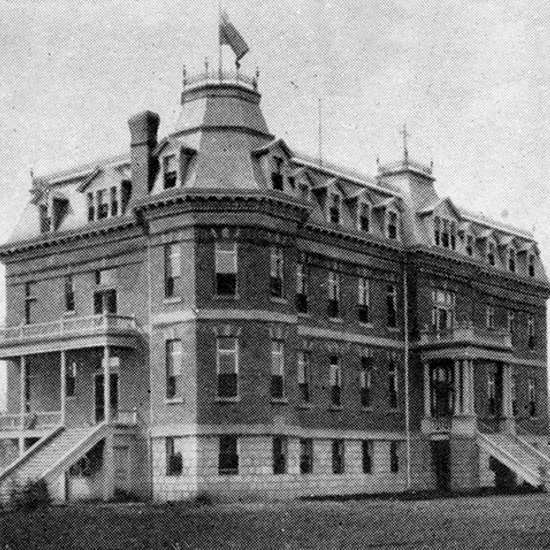

Misericordia Hospital

Oliver School

Robertson-Wesley United Church

St. Joachim's Roman Catholic Church

Valleyview Manor

Westminster Apartments

Architects

William G. Blakey

Alfred Marigon Calderon

Franz Xavier Deggendorfer

John Lang

Joseph N. Côté

Neil McKernan

Gordon Wynn

Peter Rule

John Rule

D. S. McIlroy

J. A. Senecal

George E. Turner

Edward Underwood

Unknown